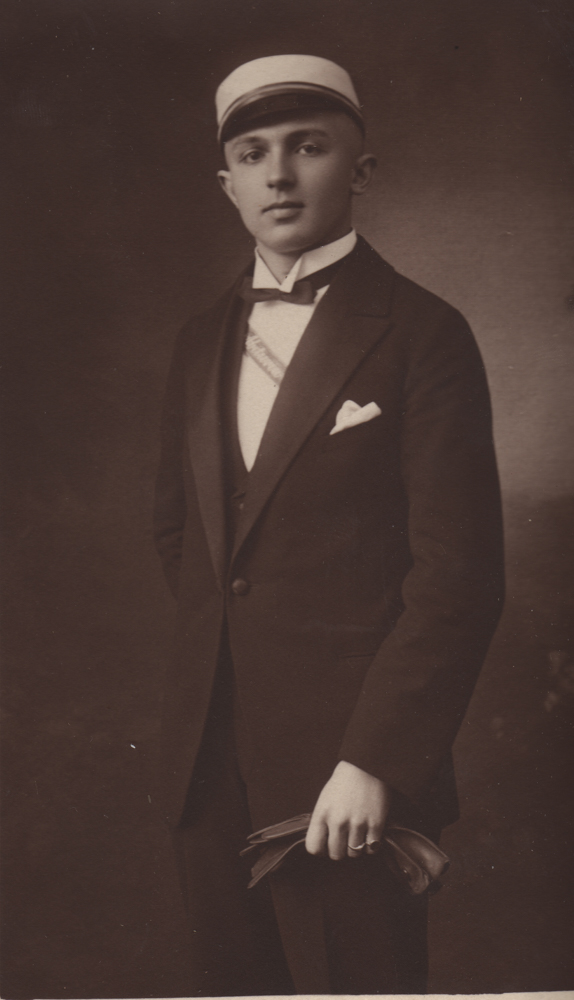

Here, Renate is talking about her cousin Werner Nennstiel, son of her [great] aunt Fanny.

I don’t remember much about Aunt Fanny’s son. He was drafted into the Wehrmacht at the beginning of the war and was later stationed in France the whole time. The few days he had during a leave from the front in Sonneberg belonged to his four boys, whose growth he was barely able to follow.

In July 1944, we had already been moving to Sonneberg for half a year1. I attended the Werner Siemens School there. Some classes were housed in the old commercial school right next to the toy museum. Sonneberg was already full of evacuees from the bombed-out German cities, and the schools were bursting at the seams.

On that memorable summer day, I did not find my mother in the kitchen as usual. No food was prepared, which by that time often consisted only of potatoes and apple sauce. We called this meagre wartime meal “Himmel und Erde”2. Of course, I immediately ran to Aunt Fanny. There I found my mother crying at the kitchen table. A sheet of paper lay in front of her, which she held out to me without saying a word.

Aunt Fanny was standing in her usual place in front of the kitchen stove. She was not crying, she was just staring into space and for the first time seemed so terribly small and lost to me. Werner, her son, was missing in France. My mother tried to console her and persuaded her that this news did not necessarily mean anything bad. In the relatively safe France, all missing persons’ fates were quickly resolved. The French would never do anything to a German occupying soldier or their friendly Werner. One should only be grateful that this bad news had not come from faraway Russia.

But Aunt Fanny never heard a word about her son’s true whereabouts. It was said that he had fallen near Avignon. The truth is that he fell into the hands of partisans, who killed him and buried him somewhere. So his mother never had even the small consolation of a grave where her Werner would have found his final resting place.

From that day on, she looked after her grandchildren even more devotedly. The three oldest were quite ruffians who often gave their grandmother a hard time. In true Nennstiel fashion, they would play the most improbable pranks. Once they blew up an entire currant bush with homemade ammunition.

Only the youngest, “Wernerle” was completely out of character. He was a very quiet, beautiful child with brown curls and big dark eyes. He was always hanging on his grandmother’s coattails while his brothers were romping about the Eller. His favorite pastime was painting. He sat very quietly on a stool at the table in the kitchen and tirelessly painted animals, flowers and sometimes even a portrait of his grandmother. He never took his little works of art home with him. His grandmother put them all in a large tin box that was once used to store Nuremberg gingerbread. The box had its place in the kitchen cupboard next to the dishes with blue and white patterns typical of Sonneberg, which no household was without.

When Wernerle started school, his grandmother gave him the most beautiful cone of sweets she had ever sewn. I say “sewn” quite deliberately, because it was actually covered with fabric, and an artfully draped rosette of light blue lace was emblazoned on the top of the opening. You can imagine how long it had been since Aunt Fanny had put a spoonful of sugar in her malt coffee so that she could conjure up at least a few sweets based on wartime recipes, which she then filled Wernerle’s cone.

One beautiful August day, little Werner was shopping with his mother. Someone gave him a black whistle, and as luck would have it, the little ball from the whistle got stuck in his windpipe. His mother ran with him in her arms to the Sonneberg hospital, which was only a few hundred meters from the Linkerhaus3, but when the desperate woman lifted her child to the doctor, little Werner could no longer be helped; he had suffocated.

His three brothers carried the small coffin to Nennstielsgrab, and there is now a separate black memorial stone for the two Werners. In front of it you can see the urn of my Greuling great-grandparents.

From then on, every summer day, late in the evening, Aunt Fanny would walk up to the church with her green watering can, behind which the large cemetery slowly rises and in the front row of which one can find, among many well-known Sonneberg names, that of little Wernerle.

- While the initial departure from Leipzig was in December 1943, it took some time before they were able to move all their belongings.

↩︎ - During World War II, “Himmel und Erde” (heaven and earth) was a practical and common meal, particularly in Germany, where food rationing and scarcity influenced daily diets. The dish’s simplicity and reliance on locally available ingredients made it suitable for wartime conditions. Wartime “Himmel und Erde” would primarily consist of potatoes and apples, as both were staples that could be grown locally, even in difficult conditions. The quality and quantity of these ingredients might have varied, with potatoes being more abundant than apples.

↩︎ - This was the residence of her parents

↩︎