But a week before the war was over for Sonneberg1, there was only one topic: would our city fathers be so sensible as to ignore the orders of the more stubborn and surrender the area without a fight? We had heard of so much senseless defense in the last few weeks, the oldest men had been called up for the national gymnastics, boys as young as 14 tried to save the Greater German Reich with the last Panzerfaust2, and the mothers were only looking for a safe hiding place where they could flee with their children if the enemy rolled in. Many packed the bare necessities and camped for days in the woods, some had a garden shed on Schönberg.

Our cellar in Bahnhofstrasse was nowhere near as solidly built as the one in Leipzig, so we sought refuge in Sonneberg’s rock cellar. The brewery owners, who had sometimes allowed us to pick up fallen fruit from their gardens, let us take shelter in a cellar3. The women sat in the corridors for three days and we children camped on the huge fermentation barrels. On them were crates of secret apples, the smell of which filled our noses, but we did not dare to take one, and the kindness of our hosts did not go so far as to part with a few apples at zero hour.

Aunt Anna was not part of the party. She did not want to leave the house under any circumstances. All her life she had helped to pack the dolls that were destined for America, and now she was supposed to flee from these Indians! That would be a laughing matter, they would definitely not do anything to her!

So once again we loaded our most valuable belongings, that is, our best clothes and a few blankets, onto a ladder cart and trudged over the Kämmleinshügel4 down to the tunnel.

The thunder of cannons was heard all around Sonneberg, and we did not believe that we would ever find our houses unscathed again. In the meantime it was clear that an idiotic district leader named Biermann5 was determined to defend the beautiful doll town down to the last house. Deep in the rock cellar we heard little of what was happening outside until three powerful impacts made even the walls of our hiding place deep in the mountain tremble. It was only hours later that we learned that the Americans had fired three warning shots at Sonneberg. One had hit the Woolworth building and set part of it on fire, the second destroyed the house – belonging to Aunt Fanny’s brother-in-law, Kohlen-Nennstiel, and the third landed in the so-called Bügeleisen, a tapering row of houses in which the W.G. Müller company had its doll factory, and where I, as a little girl, was allowed to choose my dolls in the model room.

But these three warning shots were, thank God, enough to make our entire defense strategy collapse. Sonneberg surrendered without suffering any further damage from the American army, or so we believed at the time.

After an eternity spent in our prison, we finally dared to go out onto the street. In the distance we could hear the thunder of gunfire, which was probably directed at the next town to be taken. The square in front of the Kaiser Wilhelm School was deserted. When we reached Kämmleinshügel, an American tank suddenly appeared, coming from the old town. Very slowly it rolled around the bend and towards us. Its heavy iron chains rattled loudly, and in front of the gun turret stood a black man with his legs apart and a machine gun at the ready. Very slowly he swayed his weapon from side to side. We stopped in horror at the side of the road. Now the end was coming, all three of us thought. My brother and I had never seen a living black man who looked so terrifying.

At that moment our mother was holding the handle of the ladder wagon and we were supposed to push from behind, but we just threw our arms up in the air and ran screaming into the nearest doorway, while the tank rolled very slowly past us without taking the slightest notice of us.

Mother later scolded us for our cowardice, but she also admitted that she herself had believed that her last hour had come. However, she could not lure us out of the shelter of the entrance to the house, and if old teacher Sauerteig had not come along and helped her pull her little cart up the hill, she would have been able to hold her lost post forever. It was only after some time that we both sneaked home by a roundabout route.

Aunt Anne greeted us in her usual manner. She was in complete control of the situation, had in the meantime decorated the entire residential and factory building with white cloths as a sign of surrender, as required, and had already seen a few Americans. The first thing she was accused of was our mother for hanging our best bedsheets out the window. Grandmother’s old patched ones would have done just as well as a sign of surrender.

So now the war was over for us! We climbed the stairs completely exhausted and at first could not believe that everything had passed so harmlessly. Bombs would never fall again, Sonneberg had remained intact and the Americans did not seem to be doing us any harm. Luckily for us, all we needed was a message from our father, who was now lying in a hospital somewhere.

Anne teased us for having fled to the rock cellar instead of greeting the Americans without fear like she did, and suddenly she actually pulled out from under her old apron a long, brown-wrapped object. It was a bar of Hershey chocolate. Where she had found it in such a short time was a mystery to us. Today it is impossible to imagine what a piece of chocolate meant to us back then. We had not seen a bar for years, and while my brother usually ate his share, I only ate mine a few times, and towards evening I crept into Aunt Fanny’s garden and buried a piece, wrapped in tin foil, in my tomato patch so that no one could take anything from me.

While American trucks were driving up and down Bahnhofstrasse and we were slowly getting used to the sight of them, the fire in the Woolworth building had spread further. The population stormed the huge building, regardless of the danger, after discovering that the entire complex was crammed to the roof with all kinds of army supplies. Previously, you had only been able to get in with a special permit, and now people couldn’t believe what was still there. Sacks of sugar and rice, thousands of pairs of boots, equipment from all branches of the army, buttons, nails, simply everything that had only been available on ration cards and vouchers for years. The new occupiers had actually forbidden the population to leave their homes, but there was simply no stopping the people. They rushed down Bahnhofstrasse in their hundreds to get something for themselves from the burning building. Hundreds of pounds of weight were thrown down from the upper floors, and even children were killed.

My brother and I would have loved to run down there to get something, but our mother strictly forbade us and kept us in the apartment; only the ever-intrepid Anna set off and actually came back with two pairs of paratrooper boots. They were wonderful leather shoes that reached up to the knees and were lined with lambskin, and she gave my mother a pair that warmed her feet in the cold washroom for years to come.

During this general commotion, my mother finally allowed me to look for my chocolate buried in the garden. But to my great horror, the ants had completely eaten up my treasure, which gave my brother a hell of a lot of fun, but during this short visit to the garden, something else incomprehensible happened to me. While I was still leaning over my flower bed, about five or six planes suddenly appeared on the horizon over the Eller, suddenly swooping down like hawks. I threw myself completely to the ground. The planes were now flying so low that the men on board with their machine guns could be clearly seen. Their target was the crowds on Bahnhofstrasse. They pounced on them and fired wildly into the crowd with their onboard weapons. Several Sonneberg residents were killed in the process. At first we had no idea where we were. Were they German or American planes? After all, we were already part of occupied territory. But it was apparently not that precise; the Americans advanced so quickly that several bombs continued to fall into the surrounding forests over the next few nights.

Once my brother and I looked longingly down at an American truck from the second floor of the house. It was surrounded by children, to whom the American soldiers threw something now and then. I was too cowardly to go down, but I talked my brother into it until he dared to go. He came back beaming with joy with a strange little package and a banana. He didn’t know either of them, but while he was completely happy with the chewing gum, he didn’t like the banana at all. He didn’t understand the world anymore. For years we had raved to him about these wonderful tropical fruits, and the bland-tasting thing was now a banana. He had never seen one in his life, let alone tried one, and at the time he was eight years old.

During the first few days after Sonneberg’s capitulation, we sat for hours in Aunt Fanny’s kitchen in front of her small radio, eagerly listening to every news item about the further advance of the American troops. For as long as I could remember, a picture of Billy as a baby had hung above the small radio. We would soon find out what had become of our cousin in America, but it was still a long time before a sad letter from Aunt Trude finally came across the sea, telling us about Billy’s death as a soldier in Manila.

The Woolworth building had been emptied down to the last button, and in their haste many people had grabbed things that later turned out to be pretty useless. In one of the first newspapers to appear again in Sonneberg, in addition to the orders of the military government, there were some rather strange advertisements that read something like this: Exchange 6 pairs of black left boots for three brown right boots.

In Sonneberg we were already occupied by American troops at the time of the attack on the Obersalzberg.

All in all, people slowly returned to a daily routine that was no longer part of the war, but just as little part of peace. The deprivations that people had to endure as a direct result of the catastrophic outcome of the war were too great. There was still no mail that could have brought news of our father, but we were convinced that he had managed to escape in time before the Red Army invaded.

Despite the desolate conditions at the end of the war, those of us who had survived unscathed looked to the future with hope. We in Sonneberg believed we had reason to do so when we thought about the many trade relations between our city and the USA that had existed up until the Americans entered the war.

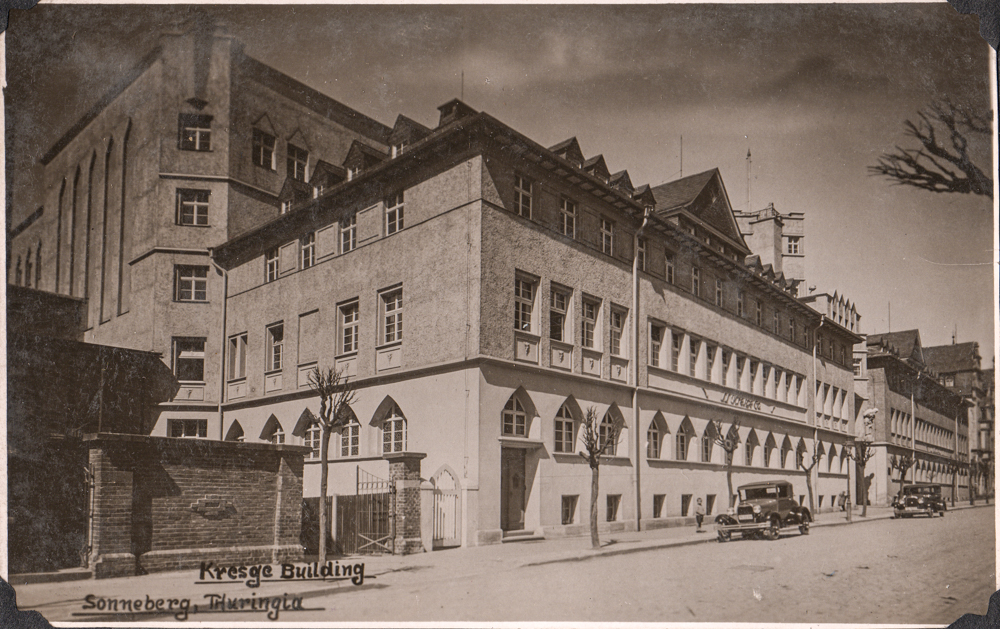

We were certain that the branches of the American department store groups Woolworth and Kresge would be rebuilt as quickly as possible, and so our occupying forces would have every interest in making Sonneberg an efficient toy town again and thus a valuable trading partner.

My family had saved more than many millions of our fellow countrymen during the war, as we had our own intact roof over our heads! And so, at the end of what was surely a long dry spell, we too saw a peaceful future for ourselves in the hometown of our ancestors.

Sonneberg would soon become what it once was.

A thriving city.

in the midst of beautiful nature.

in beautiful Thuringia,

the “Green Heart of Germany.”

- Sonneberg, Germany, fell to American forces on April 13, 1945, during the final stages of World War II. The U.S. 11th Armored Division was involved in capturing the town as Allied forces advanced into central Germany. The occupation of Sonneberg, like many others during this period, was part of the larger effort to push deeper into Nazi-held territory as the war neared its conclusion.

↩︎ - The Panzerfaust was a German anti-tank weapon used extensively during World War II. It was a shoulder-fired, single-use weapon designed to allow individual infantrymen to destroy enemy tanks.

↩︎ - Sonneberg had a tradition of brewing that involved the use of natural caves for storing beer. The caves provided an ideal environment for lagering (the process of aging beer at low temperatures), which was essential before refrigeration technology became widespread. One notable brewery in Sonneberg that utilised caves was the Sonneberger Felsenkellerbrauerei (Sonneberg Cave Cellar Brewery). The brewery used caves located in the surrounding hills, which offered a consistent, cool temperature ideal for storing their beer. These natural caves were also called “Felsenkeller,” literally translating to “rock cellars.” Such cellars were common in regions where the geography provided the necessary conditions for cool storage.

↩︎ - Kämmleinshügel is a geographical feature, specifically a hill, located in the region around Sonneberg, Germany. Kämmleinshügel is a German compound word that can be broken down into its components: [1] Kämmlein: This references a geographical feature, as “Kamm” is also used to describe a ridge or crest, such as a mountain ridge [2] Hügel: This means “hill” in German, therefore meaning: “Little Ridge Hill”.

↩︎ - There is a record of a man named Werner Biermann, who was the Kreisleiter (district leader) of Sonneberg during that period. Werner Biermann was a member of the Nazi Party and, as Kreisleiter, was responsible for the party’s activities in the Sonneberg district. After the war, as with many Nazi officials, he would have likely faced scrutiny from Allied forces during the denazification process.

↩︎ - My grandfather, who worked for the Kresge Company, was sent to Sonneberg in 1923 to oversee the building of this building. His father, max Hertha, was the Manager in charge of the Woolworths warehouse, which was bombed during the war. ↩︎