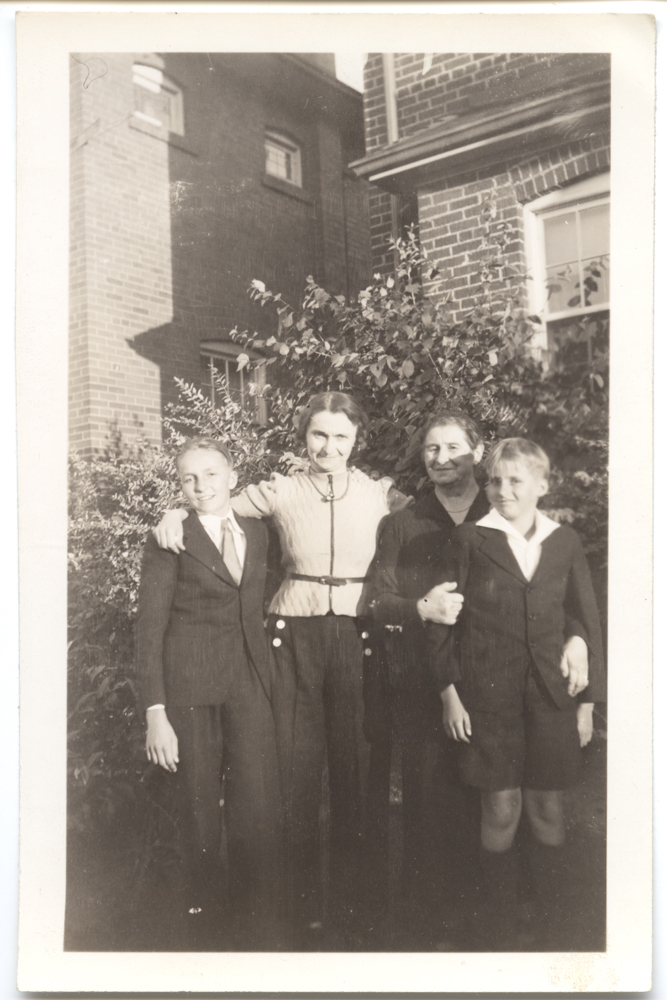

This was the home and adjoining factory of my great-grandparents, Heinrich and Berta Schellhorn1. The following is a description of that place.

We walked under the old wooden balcony, which was already dilapidated at the time, to the green-painted front door. A spacious staircase led us past two apartments up to the floor where Grandma lived. The individual steps were covered with brightly printed linoleum, which gleamed from constant polishing. There were very intricate metal rails on the thresholds for protection, which forced you to walk down the stairs with modesty, otherwise you would inevitably get caught on them and stumble.

In the dark hallway there was a massive wooden coat rack. I wouldn’t even remember it if this piece of furniture hadn’t become fashionable again in modern times. Grandma’s rack was not destined to make such a comeback. My mother was so annoyed by the old-fashioned thing that she simply sawed it up in the last winter of the war and burned it in the kitchen.

From the hallway there was a door to the kitchen on the right. It is important to note that the kitchen in Sonneberg was always the centre of domestic life. Everything happened in it, not only did people cook and eat there, but they also spent their few leisure hours there. In the absence of a bathroom, Grandma even had a large white washbasin on the wall, with cold running water. Right by the entrance on the right was the shoe bench. In this hinged wooden box were all kinds of cleaning products and rags. If our Grandma ever allowed herself a few minutes to rest, it was only on this bench. After lunch, she would sometimes sit in the corner and take a short nap before she fetched the old brown coffee grinder with the shiny brass crank from Sehr and clamped it between her knees to grind the coffee.

The old kitchen furniture consisted of a large table in the middle of the room, a white-painted cupboard and shelf, with beautifully painted milk pots of all sizes hanging on wooden knobs. Above that stood large porcelain pots on a board, on which it was written that salt, flour, sugar, semolina and barley were kept. How I would love to have at least one of these pots today, since they are so “in” again. In the left corner, a large brick stove with a water bowl, polished to a sparkling shine with oven black, caught my eye. I can see Grandmother in front of me as if it were only yesterday, warming her busy hands over the stove on cold winter days.

The fact that she never got a more modern kitchen during her lifetime was not due to her husband’s stinginess. Towards the end of the 20 years, he had beautiful kitchen furniture made for her out of larch wood. But as a real Sonneberg housewife, she did not get used to new-fangled things so quickly and the entire kitchen ended up in the attic.

When our mother spent Christmas in Sonneberg for the first time in 1929 as a young bride from Württemberg, she had been knitting diligently for a year in order to give all her new relatives a present. But no one had thought of making the new family member happy, and while Walter and Werner set off to quickly find a box of sweets, Grandmother went to the attic, fetched one of the new kitchen chairs and placed it in front of our mother, saying, “The rest is upstairs; I don’t need a new kitchen!” This furniture accompanied us on countless moves, and even today an indestructible chair serves me well when wallpapering.

From the kitchen to the right, a small door led into Anna’s room. This room was so spooky to us that we never entered it. There you could see a chest of drawers on which stood a large music box with a terrifying Negro head on it. We would have loved to hear it played but Aunt Anna always categorically explained to us that the mechanism could only be set in motion using old 2-pfennig copper pieces and that such pieces no longer existed. So we never found out what artistic pleasure we might have missed.

Grandmother told us that her sister had won this rarity at the bird shooting competition but my brother Hans later found out that she had been given it as a gift by an ardent admirer from Nuremberg. This man was her great love but unfortunately he was not good enough for the dreamer great-grandfather Greuling; his most beautiful daughter.

From the kitchen you could get to another small bedroom, where Grandmother had taken refuge because Heiner snored so miserably that the street children would curiously gather under his bedroom in broad daylight when he was taking his afternoon nap.

The largest room in the apartment, with a wonderful view down Bahnhofstrasse to the distant Mupperg, where the border now runs2, was rented to a teacher from Meiningen. I was always jealous of her pretty old secretary with the many drawers and no less jealous of her leather desk pad with green felt insert. I always had to do my homework at the old kitchen table.

But now to the grandmother’s sanctuary, the so-called salon. In my day it was never inhabited. In the old days, fun New Year’s Eve parties with huge amounts of eggnog were supposed to have taken place there, which I simply couldn’t imagine. When I sneaked in, I admired the yellowed brown photograph on the right-hand wall above an ornate sideboard. It showed the Schellhorn children Otto, Trude and Rudi, who later emigrated to America, and little Walter sitting stiffly at a table in his Sunday best.

I was also interested in a beautiful old glass cabinet, the value of which I was not yet able to estimate at the time, but which later made a wonderful journey across the border and is still in our possession today. In it, Grandma Schellhorn kept a service made of Rauenstein porcelain3 and all sorts of odds and ends. I was particularly fascinated by the Mother’s Cross4 spread out at eye level on a blue and white striped silk ribbon.

Even though I wasn’t a Hitler Youth girl in 1939, I knew that “My Führer” had given it to my grandmother for loyal service to his Reich. Today, I can’t get my head around it. Berta Schellhorn gave her children life at the peaceful turn of the century and raised them to be honest people. She never thought of making them into brave soldiers for Hitler’s armies.

In the salon there was also a chaise longue covered in wine-red plush, just like the one Loriot is seen on today on television. It was beaten thoroughly with a carpet beater every week, even though no one ever sat on it. A large picture in a heavy wooden frame hung above it. Bismarck on horseback with a spiked helmet on his head. To his right in the carriage was Napoleon III with his companions. At the bottom of the picture was a small brass plaque that read “Sedan Capitulation”5.

The small adjoining living room with a brown tiled stove was largely taken up by a piano made of reddish mahogany with two brass candlesticks. Generations of Schellhorn players struggled with this instrument. But most of them, like me, often just stared dreamily at the lid with the inscription “Rud. Ibach Sohn6” instead of practicing scales. So only my father was so skilled that people always enjoyed listening to him play. In addition to the piano, a huge wing chair covered in brown leather in this room also holds childhood memories for me. I climbed up on it not only several times a day to knock on the barometer hanging above it, which no longer knew which way it should go, but above all to have wonderful slides on it. You can imagine what Grandmother thought of that.

Two steps led through the grandparents’ bedroom to the old wooden balcony, whose windows were covered with starched white curtains that had already become somewhat rotten from the sun. A gutter ran all around the veranda, as the summer residence was called, in which one could easily have placed flower boxes like those planted with geraniums that adorn many Bavarian houses today. But back then, there was no interest in such superficialities. The outside of the balcony was adorned only by two green leafy plants, called mother-in-laws. But there is certainly a botanical term for them. These horrible things spent the winter in the stairwell, and when I sometimes complained of being bored, Grandmother would simply send me out to dust off the long cucumber-like leaves.

But Grandma Schellhorn was not just the evil grandmother. On good days she also had a heart for children and closed her two stern eyes. For all the young residents of the house, the veranda was the place of greatest delight. Our kingdom was hidden behind a Spanish wall made of rattan. There you first had to clear away several glasses of sugared oranges and lemon peel, which were used to prepare the Christmas Stollen. You also had to look after the bunches of dried mugwort hanging from the ceiling, without which no roast goose would be on the table. But then the way was clear to hat boxes, baskets and, above all, a huge suitcase. This so-called steamer trunk got its name from the fact that it had accompanied Grandma on her long journey to the USA. She was fortunate enough to see her two children living there and especially her favorite grandson Billy once again before the senseless war turned the two countries into enemies for a long time.

Billy rests in a heroes’ cemetery in Manila. He did not want to fight against his German compatriots, and so the medic was caught by low-flying Japanese planes as he was trying to help a surprised comrade7.

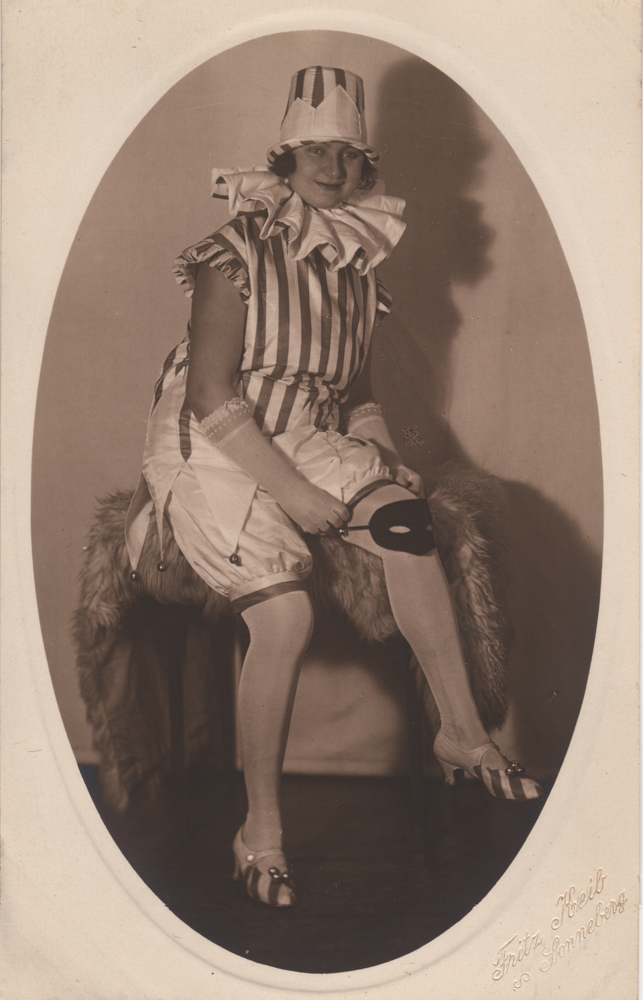

But, as is so often the case in this report, joy and sorrow lie very close together. The suitcase in question was our greatest treasure, as it contained the most heartfelt carnival costumes you could imagine. There were harlequins, Biedermeier ladies, Hungarian women, a black magic cloak and the showpiece, the Queen of the Night. Aunt Fanny won first prize in this robe at a ball. All of the masks had been sewn by the women themselves over months of work, just so that they could appear in them once. In the hat boxes we found wigs of all colors and countless hats that grandfather once dressed up in. Heiner Schellhorn was not only a member of the gymnastics, singing and shooting clubs, he also loved acting. He was a sociable man and extremely popular entertainer, only his wife, who often sat alone at her kitchen table after a hard day’s work, thought differently.

The costumes have disappeared, the steamer trunk, loaded with books, set off on its journey to Berchtesgaden many years later, and today it ekes out an existence in our attic in Schellenberg. It contains the baby equipment for my now grown-up children. Whenever I look for something in the attic and bump my head against the same roof beam for the hundredth time, my eyes fall on the old trunk and I remember the wonderful afternoons when we dressed up as princesses and clowns in a carefree childish world.

From our grandmother’s point of view, there is less good news to report about the veranda on the first floor. The tenants were a teacher couple with two children, Dieter and Jutta. Mr. Zeutschel taught at the Kaiser Wilhelm School and his wife gave piano lessons. They were pleasant, musically gifted people, but their housekeeping was often at odds with Berta Schellhorn’s meticulous cleanliness. They filled the veranda with old junk, and the one corner that was still free was turned into a small zoo by their son, much to our grandmother’s dismay. In the spring, he kept huge numbers of captured cockchafers there. He stuffed them into shoe boxes that were lined with leaves and had air holes in the lid. When Aunt Anna ran into him, he would often sneak a beetle up her skirt, for which he received many a slap in the face from the intrepid old woman. But to make matters worse, he also bred white mice, which multiplied at an unimaginable rate. I will never forget my grandmother’s horrified cry when she encountered a whole pack of escaped mice on the freshly polished steps in the stairwell.

Three little girls lived on the lower floor. To Grandma Schellhorn’s relief, they had no veranda on which they could have caused mischief. Their father was killed during the first fighting in the Russian campaign, and their mother got the children through the difficult years of the war by starting a cigarette business on the ground floor of the house. Thank God, Grandma did not live to see this set-up. The coming and going of the piano students alone caused her to sweep the stairwell twice a day. What would she have said to a wholesale deal in her sheltered middle-class home where the boxes were thrown through the living room window onto a delivery truck?

This balcony, which is still full of memories for me after all these years, almost came to a bad end in the harsh winter of 1941. The weight of the snow that had fallen in the Thuringian Forest also pressed down on the roof of the veranda, and it came loose from its anchoring to the house. The old wooden structure was leaning dangerously towards the garden and seemed to be about to collapse. Grandmother sent an urgent call for help to Leipzig, and my father8 set off to repair the damage professionally. Two long iron beams were driven out through the bedroom wall and brought the entire veranda back into place.

Our grandmother did not trust this technical invention at all and was also outraged at how it disfigured her bedroom. The iron dowels protruded a good 30cm into the room and now framed an unforgettable image on both sides.

The many cold nights I spent in the air raid shelter in Leipzig had damaged my lungs and I had to spend many a day in bed, coughing and covered with a heavy duvet. When things were particularly bad, hot potatoes were placed on my chest to help. I always had to endure it, covered up to the tip of my nose, and during these hours I had no choice but to look at the picture hanging on the wall. In old-fashioned letters it said: “Love’s Dream”. A woman of Rubensian proportions lay on a divan, only scantily covered with a veil. I never understood why Grandmother had tolerated such an indecent thing in her bedroom. Above the blissfully smiling fat lady, small cherubs armed with arrows floated down to her from sky-blue and pink clouds. Flowers of all colors were scattered everywhere, and out of boredom I kept counting them during my sweat bath.

I wasn’t very familiar with the annex that was a little further back and belonged to the factory. In peacetime, all the materials needed to make teddy bears and dolls were kept there. This included highly flammable celluloid, which had once caused a dangerous fire in Grandfather’s day. The actual cause of the fire was never fully determined, but Aunt Anna, who often haunted these rooms at night, was quite capable of handling a candle carelessly.

- In early 20th century Sonneberg, Germany, the toy manufacturing industry was characterized by a unique blend of home-based production and small-scale factories. This system, which had evolved from the 18th and 19th centuries, was integral to Sonneberg’s reputation as the “world toy city”.

The majority of toy production in Sonneberg took place in home workshops, where entire families were involved in the manufacturing process. Alongside home production, there were also small-scale factories that operated in Sonneberg. These factories were often converted residential buildings or purpose-built structures integrated into the urban landscape.

The Sonneberg toy industry was known for producing a wide variety of items, including dolls, teddy bears, stuffed animals and model trains and cars. By the early 1920s, it was estimated that about 20% of the world’s toys were manufactured in Sonneberg, leading to international recognition and the establishment of offices and warehouses by major US retail chains like Kresge and Woolworth in the town.

↩︎ - This is the border between then East and West Germany, which was in place in 1981 when this was written, but has since been removed.

↩︎ - Rauenstein porcelain refers to the products manufactured by the Rauenstein Porcelain Factory, which was established in Rauenstein, Thuringia, Germany. This factory was founded in 1784 by the Greiner family, with the permission of Duke Georg von Sachsen-Meiningen

↩︎ - The Cross of Honour of the German Mother (Ehrenkreuz der Deutschen Mutter), commonly known as the Mother’s Cross, was a state decoration in Nazi Germany. It was instituted by Adolf Hitler on December 16, 1938, to honor German mothers for their role in increasing the Aryan population. The award was part of a broader Nazi policy that emphasized traditional gender roles and aimed to encourage population growth among those considered racially pure.

The Mother’s Cross was awarded in three classes based on the number of children a mother had: Gold Cross (For mothers with eight or more children); Silver Cross (For mothers with six or seven children); Bronze Cross (For mothers with four or five children). To be eligible, mothers had to meet strict criteria, including being of “pure” German ancestry, being physically and mentally fit, and exhibiting moral probity. The award was not just for giving birth but also for raising children in accordance with Nazi ideals.

↩︎ - The Sedan Capitulation refers to the decisive military defeat of Napoleon III and the French Army during the Franco-Prussian War on September 2, 1870. This event marked a critical moment in 19th-century European history, with far-reaching consequences for France and the broader geopolitical landscape.

The French Army of Châlons, of approximately 120,000 troops was surrounded by over 200,000 German troops near the fortress town of Sedan, close to the Belgian border. After being bombarded by over 400 German artillery pieces and with all breakout attempts defeated, the French were forced to surrender. The Sedan Capitulation was essentially Napoleon III’s final political and military defeat, symbolizing the end of his imperial ambitions and dramatically altering the balance of power in Europe, particularly accelerating German unification under Prussian leadership. The Franco-Prussian war continued for 5 months after this battle.

↩︎ - Rud. Ibach Sohn was a prominent German piano manufacturer, recognized as one of the longest-running family-owned piano companies in Germany. The company was established in 1794 by Johannes Adolph Ibach in Barmen, Rhineland, Germany, and continued operations until 2007. The factory was destroyed during World War II, halting production. However, the Ibach family relaunched the business in 1952, continuing the tradition of piano manufacturing into the late 20th century

↩︎ - This is not quite true. Bill had no choice in where he was sent. According to his lieutenant, Bill was shot in the heart by enemy fire while helping a wounded comrade. No planes involved.

↩︎ - Berta’s son, Otto, was a civil engineer

↩︎