To come to conclusion as to what is a good personal accounting package is no less subjective than assessing the qualities of a fine wine, a painting, or Chinese Opera. Appreciation is subjective.

Once past the bar of functionality–taking care of debits and credits–a personal accounting package needs to be intuitive, even for those who are not accountants. It must allow importing transactions from bank accounts. It must have a Chart of Accounts (or something equivalent), and this Chart needs to provide a hierarchical depiction of the accounts. It needs to allow the automatic assignment of transactions to one, or more Accounts and, ideally, contacts (suppliers or customers). It needs to allow that when importing transactions for a credit card the sign of the amount might have to be reversed. It should allow budgeting and other “management” reports. But most important, it should have pie charts.

Yet the value proposition of such packages is questionable. First, they take a lot of time to set up and then maintain. New transaction types need to be programmed for. Flaws in the rules come to light. The Chart of Accounts gets tweaked, et cetera, et cetera. Reporting results down to the pennies encourages an ever increasing level of exactness, which drives one to want to deal with a wider and wider range of transactions, creating more and more detail. It is a cycle that never seems to end. Are these details really necessary? My wife uses a simple spreadsheet. The major problem is these packages lead to a false sense of security. Every transaction is fully coded–assigned to an account and a contact–which may then be subjected to all sorts of analysis. There is a tacit assumption that more detail leads to better result. Indeed, you can ask a bunch of interesting, but useless, questions, such as how much did I spend at restaurant X last month or over the last year? I wonder if the need to have this ability draws on some psychological insecurity? I wonder if accounting packages are targeted at a male audience?

It could certainly be argued that these tools shine a light on ones spending practice, which if nothing else might have one question their priorities. But this basic information is easily available in a simple spreadsheet.

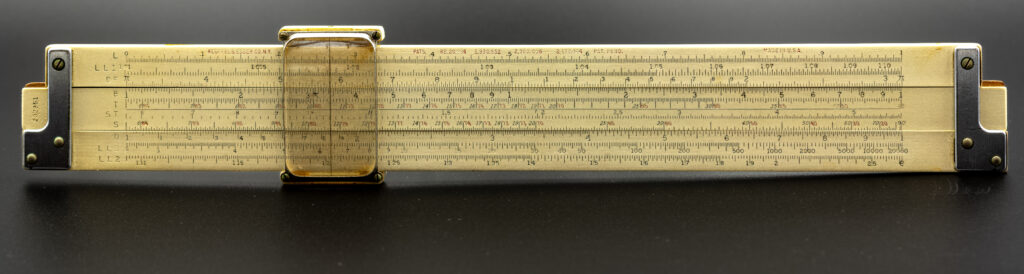

This urge towards exactness at the most detailed level is the same tendency that killed the slide rule, and when we did that, we lost a view of the big picture, of the forest, and became muddled in the darkness of the trees.

Leave a Reply